Deep generative models

Advanced Statistical Inference

EURECOM

Deep Generative Models

\[ \require{physics} \definecolor{input}{rgb}{0.42, 0.55, 0.74} \definecolor{params}{rgb}{0.51,0.70,0.40} \definecolor{output}{rgb}{0.843, 0.608, 0} \definecolor{vparams}{rgb}{0.58, 0, 0.83} \definecolor{noise}{rgb}{0.0, 0.48, 0.65} \definecolor{latent}{rgb}{0.8, 0.0, 0.8} \]\[ \require{physics} \definecolor{input}{rgb}{0.42, 0.55, 0.74} \definecolor{params}{rgb}{0.51,0.70,0.40} \definecolor{output}{rgb}{0.843, 0.608, 0} \definecolor{vparams}{rgb}{0.58, 0, 0.83} \definecolor{noise}{rgb}{0.0, 0.48, 0.65} \definecolor{latent}{rgb}{0.8, 0.0, 0.8} \]

Generative models

Given training data from an unknown distribution \(p_\text{data}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\), we want to learn a model \(p_\text{model}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) that approximates the true distribution.

Train from \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\sim p_\text{data}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

Generate from \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\sim p_\text{model}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

Latent variable models

Our objective is to learn the data distribution \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\), but we suppose that each data point \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\) is associated with a latent variable \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\).

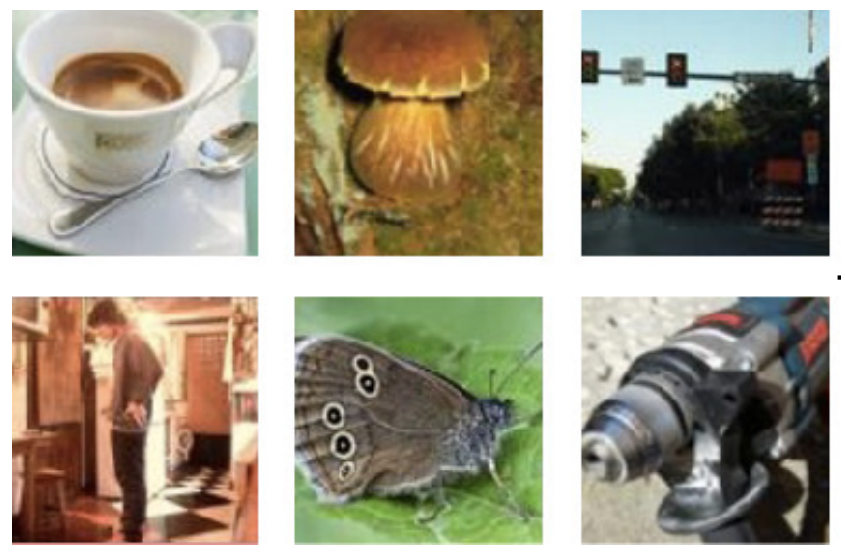

For example, image we want to learn the distribution of images of objects, like the one below:

Each image is a huge vector of pixels \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in \mathbb{R}^{H \times W \times C}\), where \(H\) is the height, \(W\) is the width and \(C\) is the number of channels (in this case, \(64 \times 64 \times 3\)).

Each image can be described by a set of 6 latent variables: floor, wall and object color, shape, orientation and scale.

Latent variable models

Latent variables are unobserved variables, we cannot measure them directly, but we can infer them from the observed data.

In math terms, we model our data distribution as a marginal of the joint distribution of the observed data and the latent variables:

\[ p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = \int p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\quad \text{or} \quad p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = \sum_{i} p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}_i) \]

where \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is the joint distribution of the observed data and the latent variables.

Linear latent variable models

Gaussian mixture model (GMM)

Conditional distribution of the data given the latent variable: \[ p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}=k) = {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\boldsymbol{\mu}}_k, {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_k) \]

where \({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_k\) and \({\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_k\) are the mean and covariance of the \(k\)-th Gaussian component.

Prior distribution of the latent variable:

\[ p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) = \text{Categorical}({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\boldsymbol{\pi}}) \]

where \(\pi_k\) are the mixing coefficients, \({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_k\) is the mean of the \(k\)-th Gaussian component, and \({\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_k\) is the covariance of the \(k\)-th Gaussian component.

Probabilistic PCA (PPCA)

Conditional distribution of the data given the latent variable: \[ p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{W}}}{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}+ {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{b}}}, \sigma^2 {\boldsymbol{I}}) \]

where \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{W}}}\) is a linear transformation matrix, \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{b}}}\) is a bias vector, and \(\sigma^2 {\boldsymbol{I}}\) is the noise covariance.

Prior distribution of the latent variable: \[ p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\boldsymbol{0}}, {\boldsymbol{I}}) \]

Variational autoencoders (VAEs)

Variational autoencoders (VAEs)

Idea:

- We want to learn a generative model \(p_\text{model}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) that approximates the true data distribution \(p_\text{data}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

- We introduce a latent variable \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) to explain the observed data \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\).

- We model the relationship between the data and the latent variable with a more complex function.

- We use a variational inference approach to learn the model parameters.

Variational autoencoders (VAEs)

Discaimer:

Variational autoencoders (VAEs) are often misrepresented as a simple autoencoder with a probabilistic twist.

This is wrong (sort of)! It hides the real nature of the encoder and decoder!

Neural networks as flexible likelihood models

Consider a maximum likelihood training objective for a generative model with latent variables:

\[ p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = \int p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}} \]

Objective: increase the flexibility of \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) to approximate the true data distribution \(p_\text{data}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

Solution: define a noisy observation model

\[ p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}), \sigma^2 {\boldsymbol{I}}) \]

where \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is a function of the latent variable \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) and the model parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\).

Note: \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is not a deterministic function, it is a probabilistic model that outputs a distribution over the data given the latent variable. If it were deterministic, then \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = 0\) almost everywhere.

Notation: we will use \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) and \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) to remember that these two distributions depend on the model parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\).

Neural networks as flexible likelihood models

\(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \int p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) is well-defined

Can we compute it?

- No, \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is very complex, so there is no hope of finding a closed-form solution.

Can we maximize it w.r.t. \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\)?

- No, we cannot compute the integral, so we cannot maximize the likelihood directly.

Solution: try to maximize a lower bound on the likelihood \(\log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\)

Jensen’s inequality

We obtain the lower bound by applying Jensen’s inequality: for any convex function \(h\) and random variable \(X\),

\[ h(\mathbb{E}[X]) \geq \mathbb{E}[h(X)] \]

Therefore, if \(h\) is concave, we have:

\[ h(\mathbb{E}[X]) \leq \mathbb{E}[h(X)] \]

The function \(\log x\) is concave, so we can apply Jensen’s inequality to obtain a lower bound on the log-likelihood:

\[ \mathbb{E} \log X \leq \log \mathbb{E} X \]

Variational inference to the rescue

We can use Jensen’s inequality to obtain a lower bound on the log-likelihood.

Suppose we have a distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) (we will see later how to choose it):

\[ \begin{aligned} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= \log \int p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\\ &= \class{fragment}{\log \int q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \frac{p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})}{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}} \\ &\geq \class{fragment}{\int q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \log \left( \frac{p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})}{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \right) \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\qquad \text{(Jensen's inequality)} }\\ &= \class{fragment}{\mathbb{E}_{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} \frac{p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})}{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} + \mathbb{E}_{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})} \end{aligned} \]

Variational inference to the rescue

Remember the Variational Inference lecture?

We can rewrite the lower bound as: \[ \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \geq \mathbb{E}_{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\right) \]

- The first term is the expected log-likelihood of the data given the latent variable. Since we assume a Gaussian model: \[ \begin{aligned} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= \log {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}), \sigma^2 {\boldsymbol{I}}) \\ &= \class{fragment}{\log \left( \frac{1}{(2\pi\sigma^2)^{D/2}} \exp\left(-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \|{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}- {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\|^2\right) \right)} \\ &= \class{fragment}{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2} \|{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}- {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\|^2 + \text{const}} \end{aligned} \]

Meaning that we want to minimize the expected reconstruction error between the data \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\) and the model output \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\), when \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) is sampled from \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\).

Variational inference to the rescue

- The second term is the KL divergence between the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) and the prior distribution \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\): \[ \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\right) = \int q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \log \frac{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})}{p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} \dd{\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}} \] This term acts as a regularizer, encouraging the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) to be close to the prior distribution \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\).

Optimization objective

\[ \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \geq \mathcal{L}_\text{ELBO}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \mathbb{E}_{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\right) \]

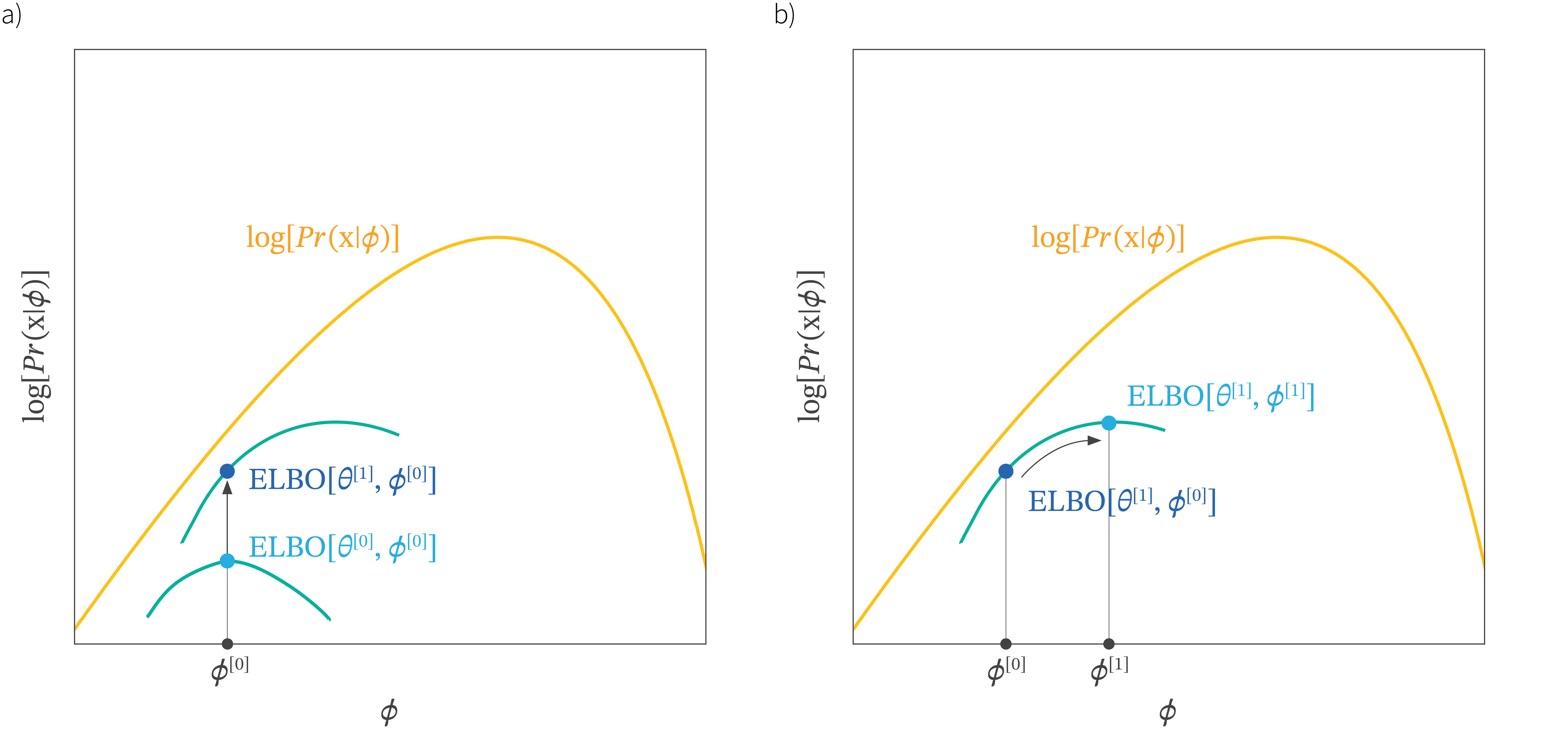

We would like to maximize the lower bound on the log-likelihood, but we want the bound to be tight

Remember that the KL divergence is always non-negative, so we can rewrite the objective as:

\[ \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \mathcal{L}_\text{ELBO}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\right) \]

This means that the closer the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is to the true posterior distribution \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\), the tighter the bound will be.

Approximate posterior inference

To fit \(q\), we need to define a variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) that approximates the true posterior distribution \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

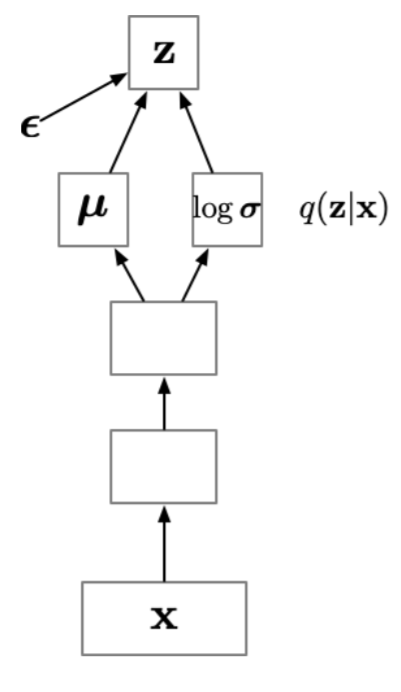

The variational distribution is often chosen to be Gaussian, i.e., \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\boldsymbol{\mu}}, {\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^2{\boldsymbol{I}})\), where \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}= \{ {\boldsymbol{\mu}}, {\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^2\}\) are the variational parameters.

Gaussian is good because it is easy to sample from, it has a closed-form KL divergence, and it is possible to use the reparameterization trick to compute gradients of the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\).

Important

The reparameterization trick allows us to sample from the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) in a way that is differentiable w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\).

\[ {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}= {\boldsymbol{\mu}}+ {\boldsymbol{\sigma}}\odot {\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}, \quad {\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}\sim {\mathcal{N}}({\boldsymbol{0}}, {\boldsymbol{I}}) \]

Training a VAE

- We need to maximize the likelihood \(\log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\). But we cannot do it directly.

- We derive a lower bound on the likelihood, the evidence lower bound (ELBO) \(\mathcal{L}_\text{ELBO}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\), which we can maximize instead. But we need to define a variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) that approximates the true posterior distribution \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

- We parametrize the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) with a Gaussian distribution, where \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}= \{ {\boldsymbol{\mu}}, {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}\}\) are the variational parameters.

At the end, we are left with the following optimization problem:

\[ \max_{{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} \mathcal{L}_\text{ELBO}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = \mathbb{E}_{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}};{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\right) \]

Note:

The ELBO is a function of both the likelihood parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\) and the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\).

The likelihood are shared across all data points, while the variational parameters are per-sample.

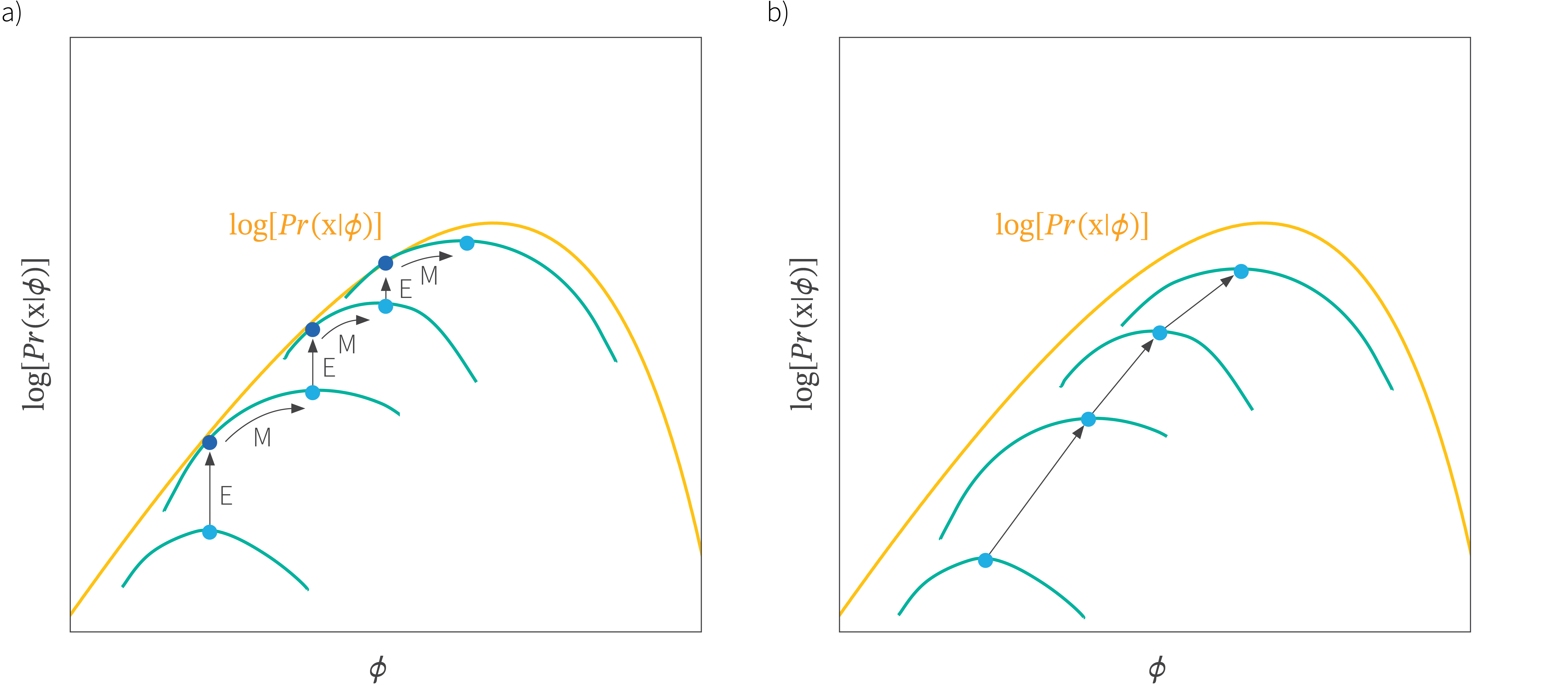

Training a VAE via joint optimization is hard

In classic VI (e.g., Bayesian logistic regression):

- ELBO depends only on \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\)

- Optimization is stable — just improve the approximation to the true posterior

In our case, for variational autoencoders:

We optimize both:

- \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\): parameters of the generative model

- \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\): variational parameters

But these two are coupled:

- ELBO depends on both sets of parameters

- Changing \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\) shifts the optimal \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\), changing \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) affects how we learn \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\).

- No close form solution for \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) given \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\) exists (no EM-like solution).

This may lead to unstable or inefficient training, especially when \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}(\cdot)\) is complex (e.g., deep neural networks).

Joint optimization of \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\) and \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\)

Expectation-Maximization vs Variational Inference

Let’s implement a VAE on MNIST (1 digit)

Amortization

In the previous approach we learn a separate set of variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) for each data point \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\).

This requires an expensive iterative optimization for each data point, which will take a long time to process large datasets.

Amortization: instead of learning a separate set of variational parameters for each data point, we learn a function \({\boldsymbol{g}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) that maps the data point \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\) to the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\).

This function is often implemented as a neural network, which allows us to learn a complex mapping from the data to the variational parameters.

Amortization

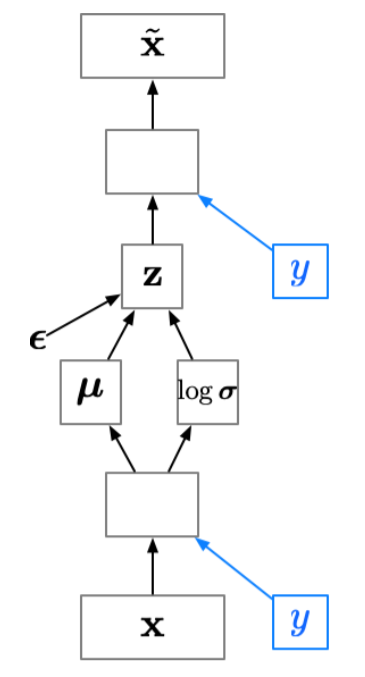

Idea: “amortize” the cost of computing the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) by learning a function that predicts \(\{ {\boldsymbol{\mu}}, {\boldsymbol{\sigma}}^2 \}\) as a function of the data \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\).

The output of this function is generally \(\textcolor{vparams}{{\boldsymbol{\mu}}}\) and \(\log\textcolor{vparams}{{\boldsymbol{\sigma}}}\) (the \(\log\) is needed to ensure that the variance is positive).

The reparametrization trick is still used to sample from the variational distribution, the only difference is that the variational parameters are not free variables anymore, but are predicted by a neural network \({\boldsymbol{g}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\).

Sometimes, this is noted as \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) to emphasize that the variational distribution depends on the data \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\), even though it’s not actually a conditional distribution.

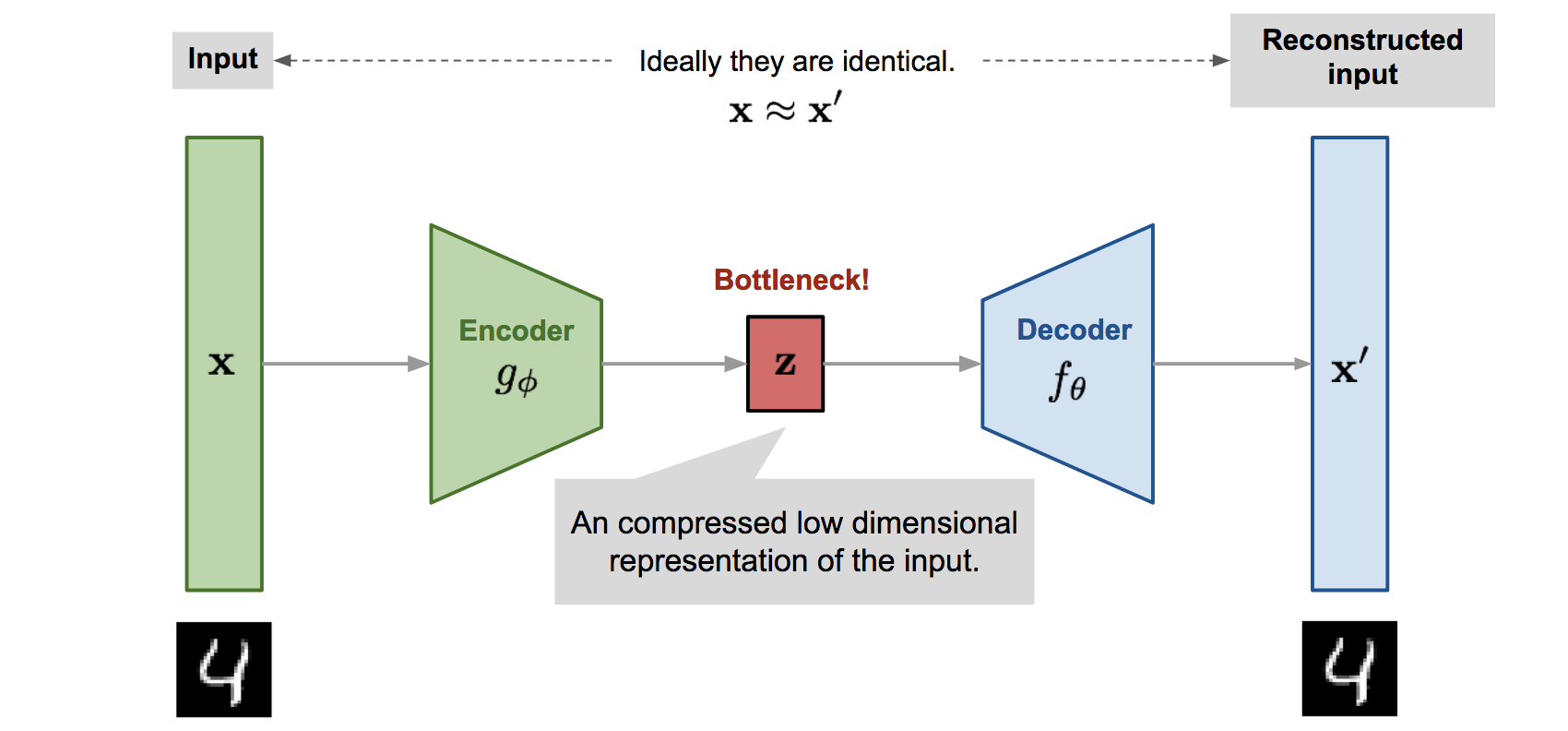

Putting it all together

We have a neural network \(g({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}})\) that predicts the variational parameters \(\{ \textcolor{vparams}{{\boldsymbol{\mu}}}, \textcolor{vparams}{{\boldsymbol{\sigma}}}^2 \}\) from the data \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\).

We can sample from the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}})\) using the reparameterization trick

We compute the likelihood \(\log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) using using a neural network \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) that maps the latent variable \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) to the data space.

We can now optimize the ELBO with respect to both the likelihood parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\) and the amortization parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}\): \[ \mathcal{L}_\text{ELBO}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}) = \mathbb{E}_{q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}})} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\right) \]

Putting it all together

Let’s train a VAE on MNIST (1 digit) with amortization

Generating samples from the VAE

Follow the generation process:

- Sample from the latent space \(z \sim p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\), where \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is the prior distribution.

- Decode the latent variable \(z\) to generate a sample \(x \sim p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) using the decoder network.

Conditional VAE (CVAE)

Sometimes we want to generate samples conditioned on some additional information \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\), e.g., we want to generate images of a specific class.

Since the latent code \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) no longer has to model the image category, it can focus on modeling the stylistic features.

If we’re lucky, this lets us disentangle style and content. (Note: disentanglement is still a dark art.)

Conditional VAE can be achieve by adding an additional input to the encoder and decoder networks, which is the additional information \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\):

Latent space analysis

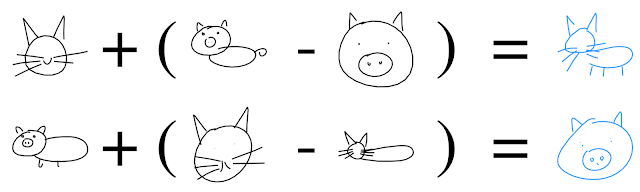

You can often get interesting results by interpolating between two vectors in the latent space:

You can also perform “arithmetic” in the latent space, e.g. by adding or subtracting vectors:

Latent space visualization

By varying two latent dimensions (i.e. dimensions of \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\)) while holding \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\) fixed, we can visualize the latent space.

Latent space interpolation

By varying the label \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\) while holding \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) fixed, we can solve image analogies.

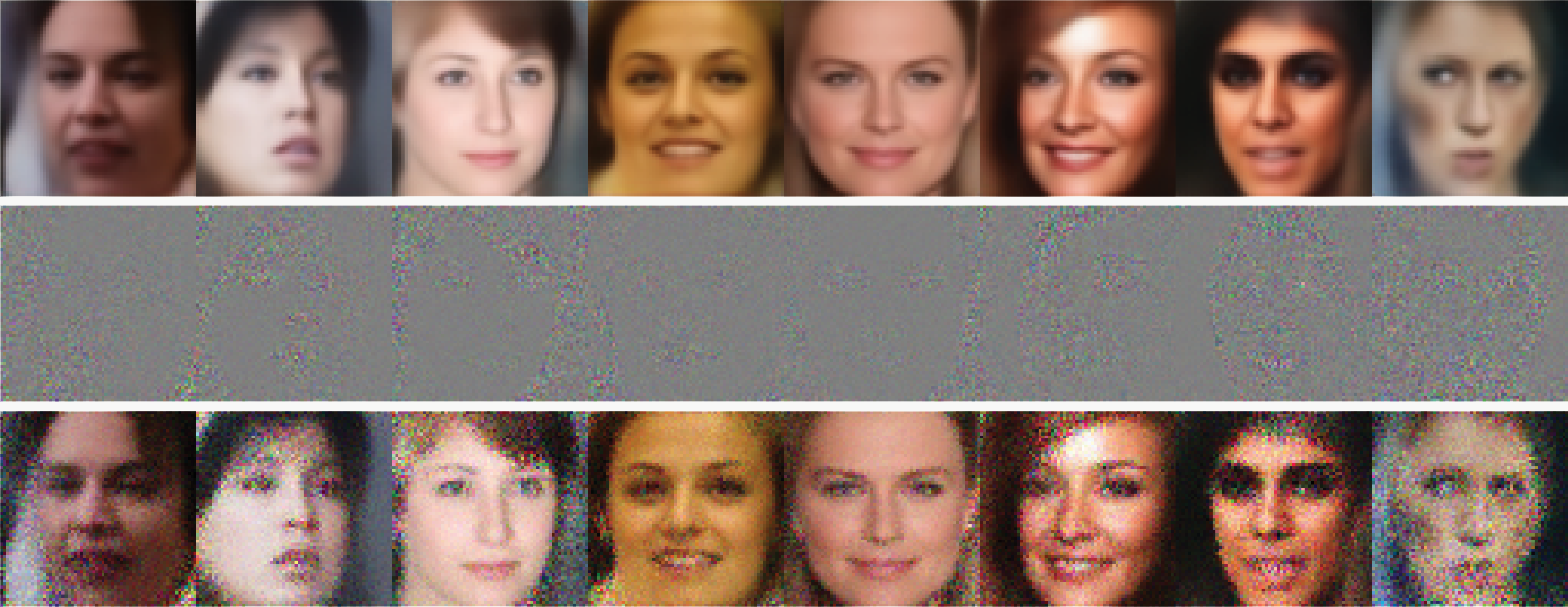

Problems with VAEs

The samples may not be very good:

VAEs suffer from mode collapse, where the amortization network learns to predict the prior. This is due to the strong effect of the KL divergence term in the ELBO.

The spherical prior \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is too restrictive, it can lead to a “blurry” output distribution (or very noisy samples, if we sample from the likelihood).

Likelihood-free generative models

Likelihood models

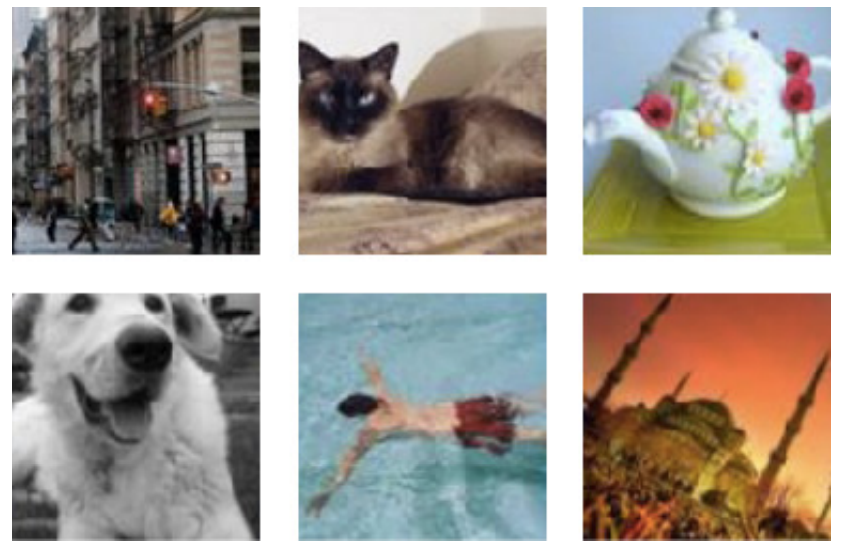

So far we have focused on likelihood-based generative models, where we maximize the likelihood of the data given the model parameters.

Likelihood-based models are powerful, but they have some limitations:

- We run on the assumption that higher likelihood means better generated samples, but this is not always true.

![]()

- We run on the assumption that higher likelihood means better generated samples, but this is not always true.

Likelihood-free learning consider alternative training objectives that do not depend directly on a likelihood

Comparing distributions via samples

\(S_1 = \{ {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_1, \ldots, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_N \mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i \sim p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) \}\)

\(S_2 = \{ {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_1, \ldots, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_N \mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_i \sim q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) \}\)

Given a finite set of samples from two distributions (\(S_1\) and \(S_2\)), how can we tell if these samples are from the same distribution or not?

Two-sample tests

Set up a statistical test to compare the two sets of samples \(S_1\) and \(S_2\):

Null hypothesis: the two sets of samples are drawn from the same distribution, i.e., \(p = q\).

Test statistic \(T\) computes a \(S_1\) and \(S_2\), for example the difference in the empirical means:

\[ T(S_1, S_2) = \frac{1}{N_1} \sum_{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in S_1} {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}- \frac{1}{N_2} \sum_{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in S_2} {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}} \]

If \(T\) is larger than some threshold \(\alpha\), we reject \(H_0\)

Key observation: Test statistic is likelihood-free since it does not depend on \(p\) and \(q\) directly, but only on the samples from these distributions.

Generative models and two-sample tests

Assume \(p_\text{data}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) is the true data distribution and we have training samples \(S_1\)

Assume we have a model \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) that permits us to generate samples for \(S_2\)

Idea: formulate the training of the generative model to minimize a two-sample test statistic between \(S_1\) and \(S_2\)

Two-sample tests are hard

Finding a good test objective in high dimensions is hard, especially when the data is complex (e.g., images).

In the generative model setup, we know that \(S_1\) and \(S_2\) come from different distributions, \(p_\text{data}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) and \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\)

Idea: Learn a statistic to automatically identify in what way the two sets of samples differ

How? Train a classifier (which we will call discriminator)

Discriminator

Build binary classifier \({\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) (e.g., neural network with parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}\)) that tries to distinguish “real” (\(\textcolor{output}{y}= 1\)) samples from the dataset and “fake” (\(\textcolor{output}{y}= 0\)) samples generated from the model

Test statistic: negative loss of the classifier.

- Low loss means real and fake samples are easy to distinguish (distributions are different).

- High loss means real and fake samples are hard to distinguish (distributions are similar).

Goal: Maximize the two-sample test statistic or equivalently minimize the classification loss.

Loss for the discriminator

Do you remember what we used for a binary classification task? Bernoulli

\[ \begin{aligned} \arg\max_{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}\mathcal{L}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}) :&= \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}} ({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})} \log {\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) + \mathbb{E}_{p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})} \log (1 - {\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})) \\ &\approx \frac{1}{N_1} \sum_{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in S_1} \log {\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) + \frac{1}{N_2} \sum_{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\in S_2} \log (1 - {\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})) \\ \end{aligned} \]

For a fixed generative model \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\), we can train the discriminator \({\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) to distinguish between real and fake samples:

- Assign probability \(1\) to real samples from the dataset \(S_1\) (i.e., from \(p_{\text{data}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\))

- Assign probability \(0\) to fake samples from the model \(S_2\) (i.e., from \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\))

Generator

Still missing: how do we generate the “fake” samples \(S_2\) from the model \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\)?

Generator:

Latent variable model with a deterministic mapping from a latent variable \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\) to the data space \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\):

- Define a function \({\textcolor{output}{G}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) as a neural network with parameters \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\)

- Sample \({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}\sim p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\), where \(p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\) is the prior distribution (e.g., Gaussian)

- Compute \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}= {\textcolor{output}{G}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})\),

How do we train the generator?

Previously we trained the discriminator to maximize the two-sample test statistic (i.e., correctly classify real and fake samples).

But for the generator, we want to minimize the two-sample test statistic (i.e., make it hard for the discriminator to distinguish between real and fake samples). \[ \min_{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\max_{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}\mathcal{L}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}) := \mathbb{E}_{p_{\text{data}} ({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})} \log {\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) + \mathbb{E}_{p({\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}})} \log (1 - {\textcolor{output}{D}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\phi}}}, {\textcolor{output}{G}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{latent}{\boldsymbol{z}}}))) \] This is a minimax optimization problem

Generative adversarial networks (GANs)

This model configuration and training procedure is known as Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

Generative adversarial networks (GANs)

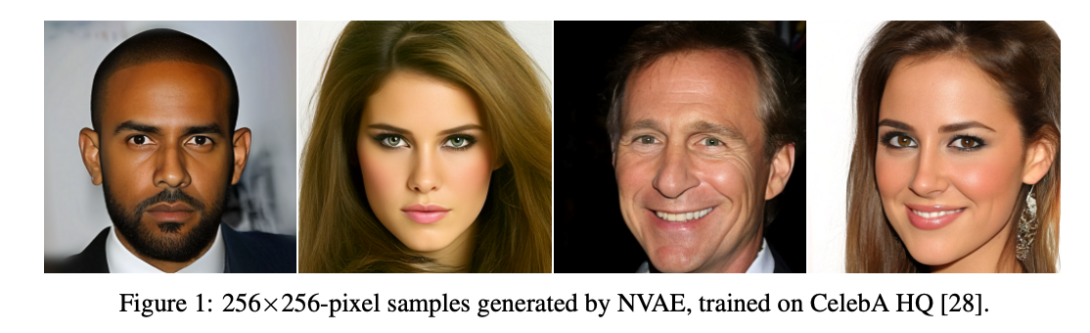

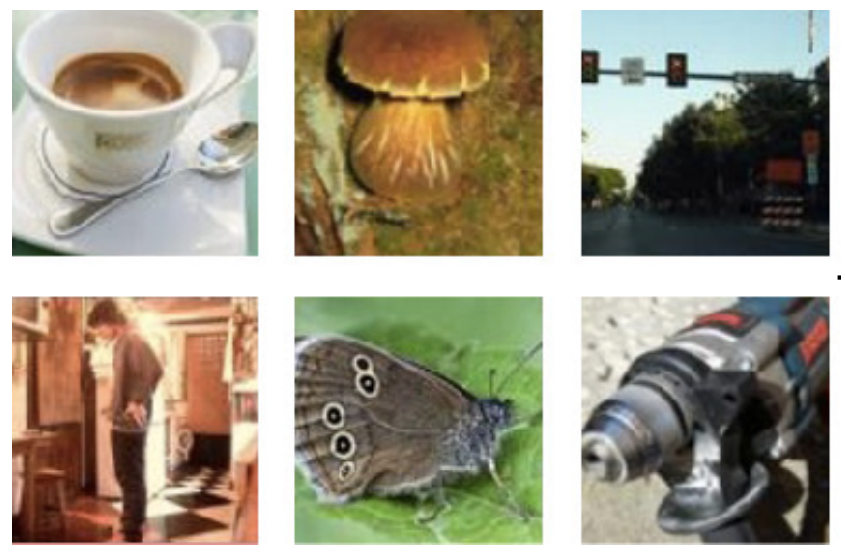

GANs have been successfully applied to several domains and tasks

Generative adversarial networks (GANs)

Pros:

- Loss only requires samples, no likelihood needed

- Lots of flexibility in the choice of the neural network architecture for the generator and discriminator

- Can generate high-quality samples

- Fast sampling from the model (just sample from noise and pass through the generator)

Cons:

- Training is unstable, they are hard to train

- No guarantee that the generator will learn the true data distribution (see Nash equilibrium)

- Hard to numerically evaluate the quality of the generated samples (no likelihood, no ELBO)

Training GANs is hard (intuition)

Imagine \(f(x, y) = xy\) and we want to comput \(\min_x \max_y f(x, y)\). A gradient descent ascent algorithm would look like this:

\[ \begin{aligned} x &\gets x - \eta \nabla_x f(x, y) = x - \eta y\\ y &\gets y + \eta \nabla_y f(x, y) = y + \eta x \end{aligned} \]

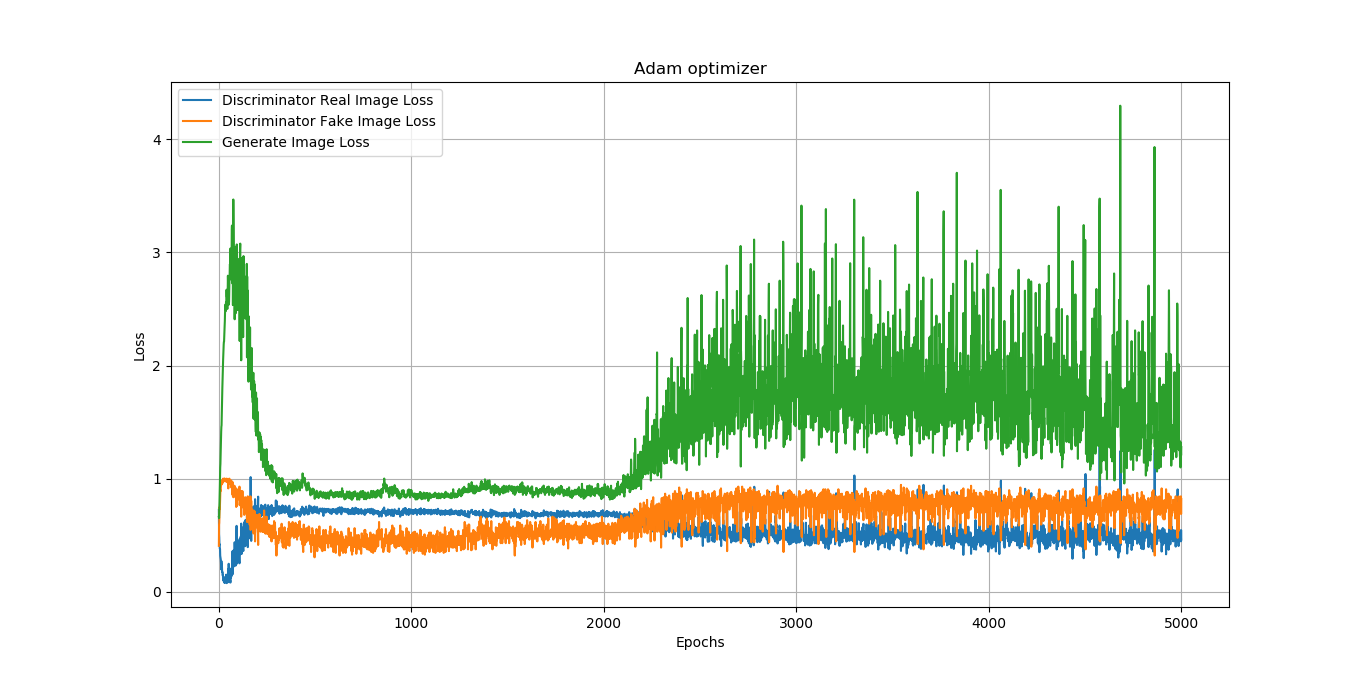

Training GANs is hard

The generator and discriminator loss keep oscillating during GAN training

Difficult to assess if training is converging or not

![]()

Diffusion models

Diffusion models

Currently the state-of-the-art generative models, especially for image/video generation tasks

Diffusion models

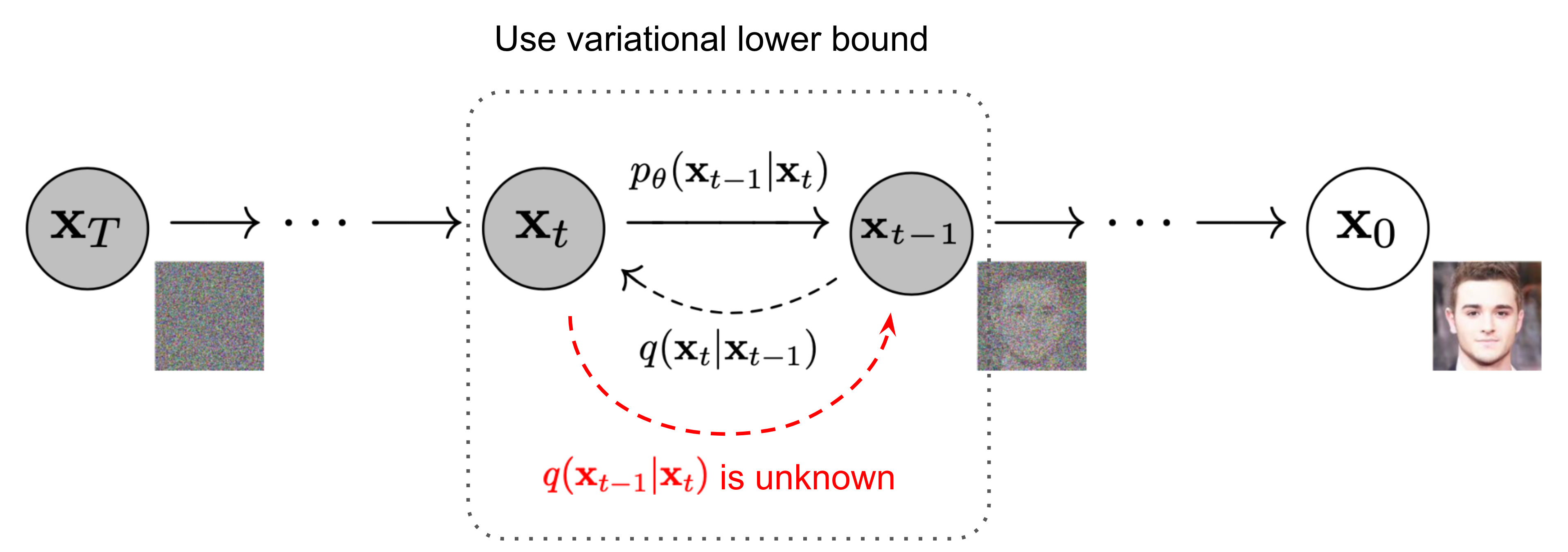

Key idea: corrupt the data \({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\) into noise by adding Gaussian noise in a series of steps, and then learn to reverse this process to generate new samples.

For example:

\[ q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t \mid {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{t-1}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t; \sqrt{1 - \beta_t} {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{t-1}, \beta_t {\boldsymbol{I}}) \]

where \(\beta_t\) is a small positive constant that controls the amount of noise added at each step.

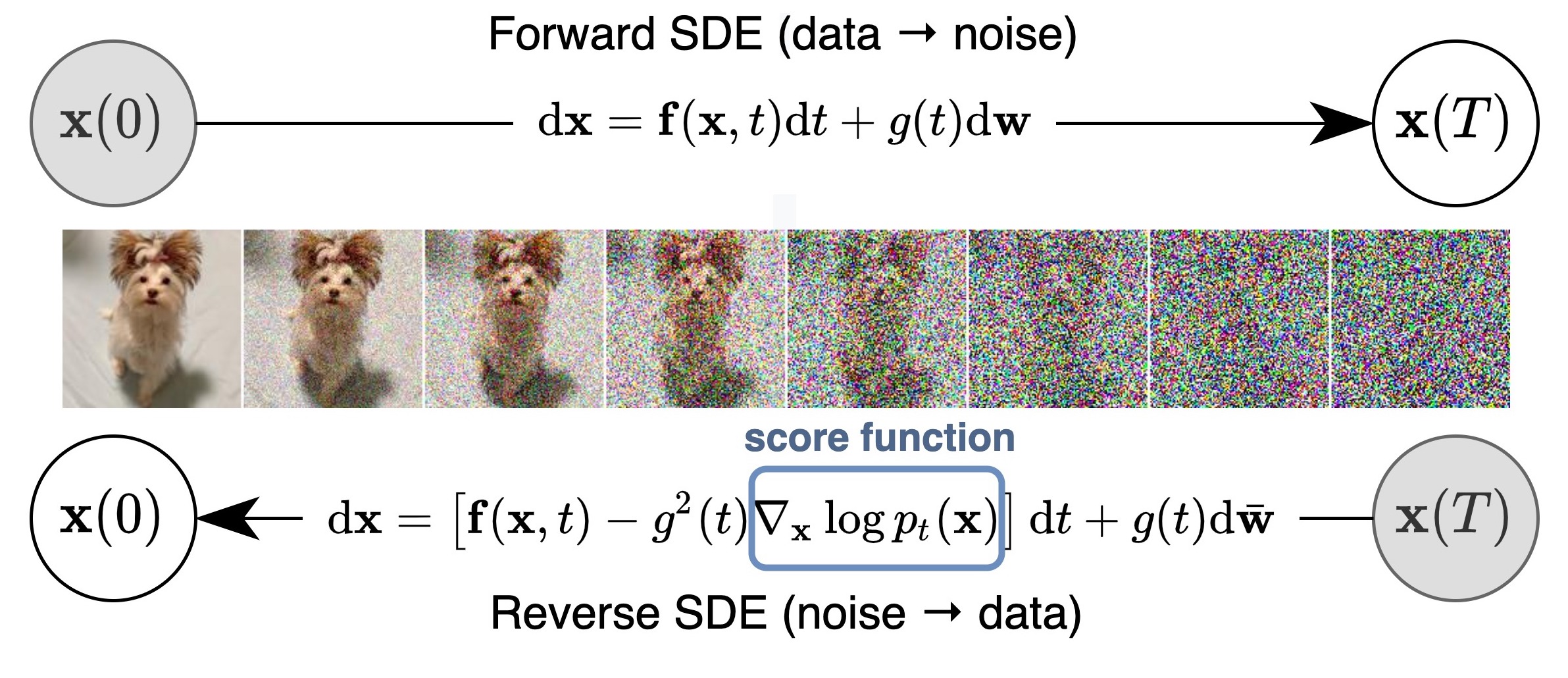

Continuous diffusion process

The diffusion process can be viewed as a continuous-time stochastic process, described by a stochastic differential equation (SDE) of the form:

\[ \dd{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t = {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t, t) \dd t + \textcolor{output}{g}(t) \dd {\boldsymbol{B}}_t \]

Reverse diffusion process

The reverse diffusion process is also described by an SDE:

\[ \dd{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t = \left({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{f}}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t, t) - \textcolor{output}{g}(t)^2 \nabla_{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t)\right) \dd t + \textcolor{output}{g}(t) \dd {\boldsymbol{B}}_t \]

Training diffusion models

To train the diffusion model, we learn a neural network \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{s}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, \cdots)\) to approximate the score function \(\nabla_{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t} \log p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}_t)\):

\[ \text{KL}\left(p_0({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}; {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \leq \frac{T}{2}\mathbb{E}_{t \in \mathcal{U}(0, T)}\mathbb{E}_{p_t({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})}[\lambda(t) \| \nabla_{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}\log p_t({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) - {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{s}}}({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}, {\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}, t) \|_2^2] + \text{KL}\left(p_T({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) \parallel p_{\text{prior}}({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\right) \]

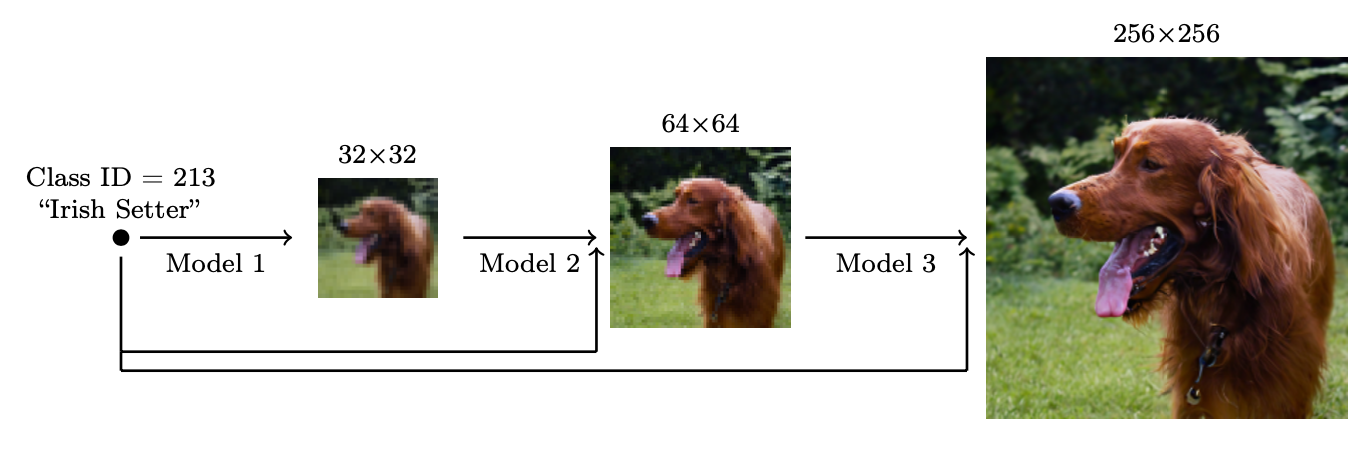

Flexibility of diffusion models: super-resolution

High-resolution samples starting from low-resolution noise:

Flexibility of diffusion models: inpainting

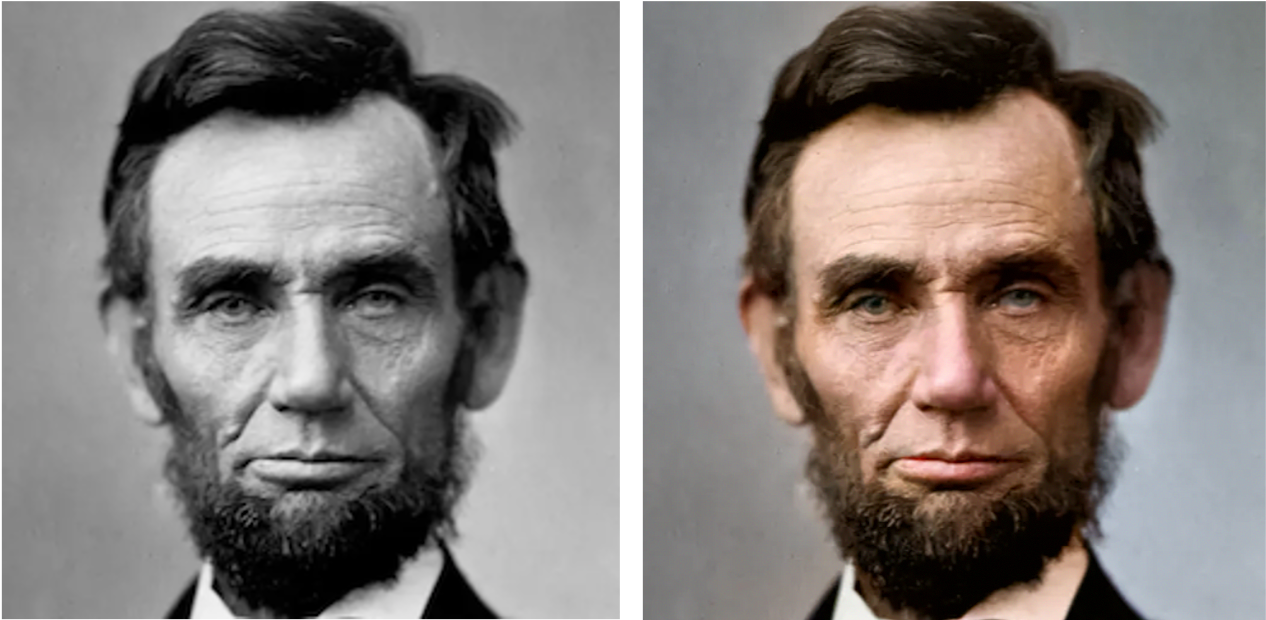

Flexibility of diffusion models: colorization

Flexibility of diffusion models: text-to-image

Prompt: Produce a stunning, award-winning close-up of a chameleon blending into a background of vibrant, textured leaves, its eye swivelled to look directly at the camera. The intricate texture of its skin changing colour is the focus (visceral adaptation). Abstract dappled light filters through the leaves. Inspired by wildlife macro photography and camouflage patterns.

Prompt: Cinematic shot using a stabilized drone flying dynamically alongside a pod of immense baleen whales as they breach spectacularly in deep offshore waters. The camera maintains a close, dramatic perspective as these colossal creatures launch themselves skyward from the dark blue ocean, creating enormous splashes and showering cascades of water droplets that catch the sunlight. In the background, misty, fjord-like coastlines with dense coniferous forests provide context. The focus expertly tracks the whales, capturing their surprising agility, immense power, and inherent grace. The color palette features the deep blues and greens of the ocean, the brilliant white spray, the dark grey skin of the whales, and the muted tones of the distant wild coastline, conveying the thrilling magnificence of marine megafauna.

Simone Rossi - Advanced Statistical Inference - EURECOM