Introduction to Variational Inference

Advanced Statistical Inference

EURECOM

Introduction to Variational Inference

\[ \require{physics} \definecolor{input}{rgb}{0.42, 0.55, 0.74} \definecolor{params}{rgb}{0.51,0.70,0.40} \definecolor{output}{rgb}{0.843, 0.608, 0} \definecolor{vparams}{rgb}{0.58, 0, 0.83} \definecolor{noise}{rgb}{0.0, 0.48, 0.65} \definecolor{latent}{rgb}{0.8, 0.0, 0.8} \]

\[ \require{physics} \definecolor{input}{rgb}{0.42, 0.55, 0.74} \definecolor{params}{rgb}{0.51,0.70,0.40} \definecolor{output}{rgb}{0.843, 0.608, 0} \definecolor{vparams}{rgb}{0.58, 0, 0.83} \definecolor{noise}{rgb}{0.0, 0.48, 0.65} \]Refresher: Kullback-Leibler Divergence

The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence is a measure of how one probability distribution diverges from a second

Given two probability distributions \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\) and \(q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\), the KL divergence is defined as

\[ \text{KL}\left(q \parallel p\right) = \int q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) \log \frac{q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})}{p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})} \dd{{\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}} = {\mathbb{E}}_q \left[ \log \frac{q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})}{p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})} \right] \]

Properties

- \(\text{KL}\left(q \parallel p\right) \geq 0\) with equality if and only if \(q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\)

- \(\text{KL}\left(q \parallel p\right) \neq \text{KL}\left(p \parallel q\right)\), i.e., it is not symmetric

- It’s not a true distance measure as it’s not symmetric and doesn’t satisfy the triangle inequality

Asymmetry of KL Divergence

KL divergence for Gaussians

The KL divergence between two Gaussians is tractable and has a closed-form solution

For two Gaussian distributions \(p(x) = {\mathcal{N}}(\mu_p, \sigma_p^2)\) and \(q(x) = {\mathcal{N}}(\mu_q, \sigma_q^2)\):

\[ \text{KL}\left(q \parallel p\right) = \frac{1}{2} \left( \frac{\sigma_p^2}{\sigma_q^2} + \frac{(\mu_q - \mu_p)^2}{\sigma_q^2} - 1 + \log \frac{\sigma_p^2}{\sigma_q^2} \right) \]

- For two multivariate Gaussians \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_p, {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_p)\) and \(q({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_q, {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_q)\):

\[ \text{KL}\left(q \parallel p\right) = \frac{1}{2} \left( \tr({\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_q^{-1} {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_p) + ({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_q - {\boldsymbol{\mu}}_p)^\top {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_q^{-1} ({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_q - {\boldsymbol{\mu}}_p) - k + \log \frac{\det {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_q}{\det {\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_p} \right) \]

Exercise

Simplify the expression when \({\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}_p = \sigma_p^2 {\boldsymbol{I}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{\mu}}_p = {\boldsymbol{0}}\).

Jensen’s Inequality

- Another important result is Jensen’s inequality, which states that for any convex function \(f\) and random variable \(X\): \[ {\mathbb{E}}[f(X)] \geq f({\mathbb{E}}[X]) \]

For example, if \(f(x) = \log x\), then:

\[ {\mathbb{E}}[\log X] \leq \log({\mathbb{E}}[X]) \]

Variational Inference

Introduction to Variational Inference

Remember: given a likelihood \(p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) and a prior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\), we want to compute the posterior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\), which is intractable in most cases.

- Variational Inference (VI) is a method for approximating intractable posterior distributions

Intuition: Instead of trying to solve intractable integrals, we solve an optimization problem

Sketch of the recipe

- Choose a family of distributions \(\mathcal Q\) to approximate the posterior

- Define an objective function to measure the quality of the approximation

- In the set of distributions \(\mathcal Q\), find the one that minimizes the objective function

Variational Inference: A Simple Example

Variational Inference: Form of the Approximation

Form of the Approximation

What family of distributions \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\) should we choose to approximate the posterior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\)?

- Mean-field approach: each parameter \(\textcolor{params}\theta_j\) is independent and has its own distribution \[ q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \prod_{j=1}^J q_j(\textcolor{params}\theta_j) \]

For simplicity:

- all \(q_j(\textcolor{params}\theta_j)\) are Gaussian distributions, i.e., \(q_j(\textcolor{params}\theta_j) = q(\textcolor{params}\theta_j) = {\mathcal{N}}(\textcolor{vparams}m_j, \textcolor{vparams}s_j^2)\)

- each parameter \(\textcolor{params}\theta_j\) has its own mean \(\textcolor{vparams}m_j\) and variance \(\textcolor{vparams}s_j^2\)

\[ q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \prod_{j=1}^J {\mathcal{N}}(\textcolor{vparams}\mu_j, \textcolor{vparams}\sigma_j^2) \]

\({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}= \{\textcolor{vparams}m_j, \textcolor{vparams}s_j^2\}\) are called the variational parameters

The goal is to find the optimal values of \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) \(\Rightarrow\) best approximation \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) to the true posterior

Defining the Objective Function

Objective Function

- How to define the quality of the approximation \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\)?

- We use the KL divergence between the approximate distribution \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) and the true posterior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\)

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\right) &= \int q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \log \frac{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})}{p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})} \dd{{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} \\ &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \left[ \log \frac{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})}{p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})} \right] \end{aligned} \]

Problem

- This expression is still intractable because the posterior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\) is unknown

- We need to find a way to approximate the KL divergence

Manipluating the expression:

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\right) &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) - {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}) \\ &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) - {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log \frac{p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})}{p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})} \\ &= \underbrace{{\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})}_{\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 1}\kern .3em}} - \underbrace{{\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})}_{\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 2}\kern .3em}} - \underbrace{{\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})}_{\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 3}\kern .3em}} + \underbrace{\log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})}_{\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 4}\kern .3em}} \end{aligned} \]

Breakdown:

\(\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 1}\kern .3em}\): entropy of the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\)

\(\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 2}\kern .3em}\): expected log-likelihood of the data under the variational distribution

\(\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 3}\kern .3em}\): cross-entropy between the variational distribution and the prior

\(\bigcirc\llap{\text{\small 4}\kern .3em}\): log marginal likelihood of the data

Rearranging the terms:

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\right) &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) - {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) + \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}) \\ &= -{\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) + \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) + \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}) \end{aligned} \]

This is an important equation in variational inference!

Note: The term \(\log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\) is a constant w.r.t. \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\). Let’s move it to the left:

\[ \begin{aligned} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\right) &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

Now the right-hand side is computable: it’s called Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO)

\[ {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \]

ELBO: Evidence Lower Bound

\[ \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\right) = {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \]

- Minimizing the KL divergence is equivalent to maximizing the ELBO

- The KL divergence is non-negative:

- \({\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \leq \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\)

- \({\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) is a lower bound on the marginal likelihood of the data

- If \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\), then \({\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\)

ELBO to be maximized w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\):

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

- The first term is a model fitting term:

- It encourages the model to explain the data well

- The higher, the better the parameters drawn from \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) are at explaining the data

- The second term is a regularization term:

- It encourages the variational distribution to be close to the prior

- The lower, the closer the variational distribution is to the prior

Computing the ELBO: Regularization Term

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

Recall our assumption that the variational distribution is a product of Gaussians \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \prod_{j=1}^J {\mathcal{N}}(\textcolor{vparams}m_j, \textcolor{vparams}s_j^2)\)

The second term in the ELBO is the KL divergence between the variational distribution and the prior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) = \prod_{j=1}^J {\mathcal{N}}(0, \sigma^2)\)

The KL divergence between two Gaussians is tractable and has a closed-form solution

\[ \begin{aligned} \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) &= \frac 1 2 \sum_{j=1}^J \left( \frac{\textcolor{vparams}s_j^2}{\sigma^2} + \frac{\textcolor{vparams}m_j^2}{\sigma^2} - 1 + \log \frac{\sigma^2}{\textcolor{vparams}s_j^2} \right) \end{aligned} \]

Computing the ELBO: Model Fitting Term

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) &= {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

- The first term is more complex to compute and only analytically available for simple models, but …

- … we can use Monte Carlo methods to estimate it

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &\approx \frac 1 S \sum_{s=1}^S \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)}) \end{aligned} \]

where \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)} \sim q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\)

Note: This estimation is unbiased and its variance decreases with \(\propto 1/S\), independent of the dimensionality of \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\)!

ELBO Optimization

ELBO Optimization

Review:

- We chose a family of distributions \(\mathcal Q\) to approximate the posterior (\(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = \prod_{j=1}^J {\mathcal{N}}(\textcolor{vparams}m_j, \textcolor{vparams}s_j^2)\))

- We defined the ELBO as the objective function to measure the quality of the approximation \[ {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \]

- We discussed how to compute the regularization term and the model fitting term

- We need to optimize the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\)

\[ \begin{aligned} {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}^* &= \arg\max_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \\ &= \arg\max_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

An overview of VI optimization algorithms

VI algorithms can be divided into two categories:

- Coordinate Ascent Variational Inference (CAVI):

- Optimize each variational parameter \(\textcolor{vparams}\nu_j\) separately

- Gradient-based Variational Inference:

- Use gradient-based optimization methods to optimize the variational parameters simultaneously

Gradient-based methods comes in different flavors:

- Black-box Variational Inference (BBVI)

- Reparameterization Gradients (RG)

- Stochastic Variational Inference (SVI)

- Automatic Differentiation Variational Inference (ADVI)

- Amortized Variational Inference

Optimizing the ELBO is hard

Let’s consider the optimization problem:

\[ \begin{aligned} {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}^* &= \arg\max_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \\ &= \arg\max_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

We need to compute the gradient of the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\):

\[ \begin{aligned} \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) &= \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) - \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} \text{KL}\left(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \parallel p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\right) \end{aligned} \]

Problem

We cannot move the gradient inside the expectation because the expectation is w.r.t. the variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\)

REINFORCE: The Score Function Gradient Estimator

The Score Function Gradient Estimator (REINFORCE) is a general method to estimate gradients of expectations

Log-derivative trick:

\[ \begin{aligned} \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) &= q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \end{aligned} \]

Derivation

Derive the expression above using the chain rule

\[ \begin{aligned} \grad_{{\boldsymbol{z}}} \log f({\boldsymbol{z}}) &= \frac{\grad_{{\boldsymbol{z}}} f({\boldsymbol{z}})}{f({\boldsymbol{z}})} \end{aligned} \]

Then, rearrange the terms

REINFORCE: The Score Function Gradient Estimator

Using the log-derivative trick, we can rewrite the gradient of the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\):

\[ \begin{aligned} \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= \int \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \dd{{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} \\ &={\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \\ &\approx \frac 1 S \sum_{s=1}^S \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} \log q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \end{aligned} \]

where \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)} \sim q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\).

REINFORCE: The Score Function Gradient Estimator

Pros

- Easy to implement

- Only requires the gradient of the log-density of the variational distribution

- Can be used for any model (hence the name “black-box”)

Cons

- High variance

- Slow convergence

- Needs additional variance reduction techniques

- Not popular for (modern) variational inference

Reparameterization Trick

Objective: \(\grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\)

Idea: Freeze the randomness in the variational distribution

- Samples from \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) are generated by a deterministic transformation \(t\) of a random variable \({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}\sim p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})\)

- The variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) are parameters of the transformation \(t\)

- The gradient of the expectation w.r.t. the variational parameters can be computed using the chain rule

Gaussian Example

For a Gaussian variational distribution \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}_i;{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}(\textcolor{vparams}m_i, \textcolor{vparams}s_i^2)\)

- \(p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}) = {\mathcal{N}}(0, 1)\)

- \(t({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) = \textcolor{vparams}m_i + \textcolor{vparams}s_i {\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}\)

Reparameterization Trick: Derivation

Key observation

For a generic function \(f({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\), we have \[ \begin{aligned} \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} f({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})} f({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \end{aligned} \]

with \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}= t({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\). Now the expectation is w.r.t. the random variable \({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}\) and the gradient can be moved inside the expectation

For the ELBO:

\[ \begin{aligned} \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathbb{E}}_{p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \\ &\class{fragment}{{} = {\mathbb{E}}_{p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})} \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})} \\ &\class{fragment}{{} = {\mathbb{E}}_{p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})} \grad_{{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} \\ &\class{fragment}{{} = {\mathbb{E}}_{p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})} \grad_{{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} t({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \\ &\class{fragment}{{} \approx \frac 1 S \sum_{s=1}^S \grad_{{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)}) \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} t({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}^{(s)}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \end{aligned} \]

where \({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}^{(s)} \sim p({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}})\) and \({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}^{(s)} = t({\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}^{(s)}; {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\).

Reparameterization Trick: Pros and Cons

Pros

- Low variance

- Fast convergence

- No need for additional variance reduction techniques

- Popular in many models (like autoencoders)

Cons

- Requires reparameterization of the variational distribution

- Needs the model/likelihood to be differentiable

Reparameterization Gradients vs REINFORCE

Comparison of the gradients of the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters using the Reparameterization Gradients and REINFORCE

Stochastic Gradient Optimization

The gradient of the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) are stochastic but unbiased

\[ {\mathbb{E}}_{\text{noise}} \widetilde{\grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} = \grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}) \]

Variational inference with stochastic optimization

- Stochastic optimization has a long history and good theoretical properties about convergence

- Optimizing using stochastic updates reaches local optima if the learning rate \(\alpha_t\) goes to zero with a certain rate (Robbins-Monro conditions)

\[ \begin{aligned} \sum_i^T \alpha_i = \infty \quad \text{and} \quad \sum_i^T \alpha_i^2 < \infty \end{aligned} \]

- Price: Covergence in \(\mathcal{O}(1/\sqrt{T})\) where \(T\) is the number of iterations, vs \(\mathcal{O}(1/T)\) with exact gradients (when available)

Convergence of Stochastic Optimization

\[ \begin{aligned} {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}_{t+1} &= {\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}_t + \alpha_t \widetilde{\grad_{{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}} {\mathcal{L}}_{\text{ELBO}}({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}_t)} \end{aligned} \]

Summary

- Variational Inference (VI) is a method for approximating intractable posterior distributions

- The goal is to find the best approximation \(q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})\) to the true posterior \(p({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}\mid {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}})\)

- The quality of the approximation is measured using the Evidence Lower Bound (ELBO)

- Optimizing the ELBO w.r.t. the variational parameters \({\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}}\) is challenging:

- The gradients of the ELBO are generally intractable

- We can use Monte Carlo methods to estimate the gradient

Extensions

Extensions of Variational Inference

- Mini-batch optimization

- More complex variational families

Mini-batch Optimization

Likelihood term in the ELBO: \({\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}})\)

If the likelihood factorizes over the data points (data points are independent):

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= \sum_{i=1}^N {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}_i\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \end{aligned} \]

Problem:

- We need to compute the expectation over the variational distribution for each data point

- For large datasets, this can be computationally expensive

Solution: Use mini-batches of data points to estimate the expectation

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &\approx \frac N B \sum_{b=1}^B {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}_i\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \quad \text{with} \quad B \ll N \end{aligned} \]

Mini-batch Optimization

\[ \begin{aligned} {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &\approx \frac N B \sum_{b=1}^B {\mathbb{E}}_{q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}};{\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\nu}}})} \log p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}_i\mid{\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) \end{aligned} \]

Pros: - Faster convergence - Scalable to large datasets

But double source of stochasticity:

- Monte Carlo estimation of the expectation

- Mini-batch optimization

More Complex Variational Families

Mean-field assumption: each parameter \(\textcolor{params}\theta_j\) is independent and has its own distribution

Problem: The mean-field assumption can be too restrictive \(\Rightarrow\) we can use more complex variational families

If we make the variational family more complex, we get better approximation to the true posterior

Gaussian with Full Covariance

Instead of assuming that the parameters are independent, we can assume that they are correlated

- The variational distribution is a multivariate Gaussian with full covariance matrix

\[ \begin{aligned} q({\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}) &= {\mathcal{N}}(\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\mu}}, \textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}) \end{aligned} \]

- Reparameterization trick is still applicable using the Cholesky decomposition \(\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\Sigma}}= \textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{L}}\textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{L}}^T\)

\[ \begin{aligned} {\textcolor{params}{\boldsymbol{\theta}}}&= \textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{\mu}}+ \textcolor{vparams}{\boldsymbol{L}}{\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}, \quad \text{with} \quad {\textcolor{noise}{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}}\sim {\mathcal{N}}({\boldsymbol{0}}, {\boldsymbol{I}}) \end{aligned} \]

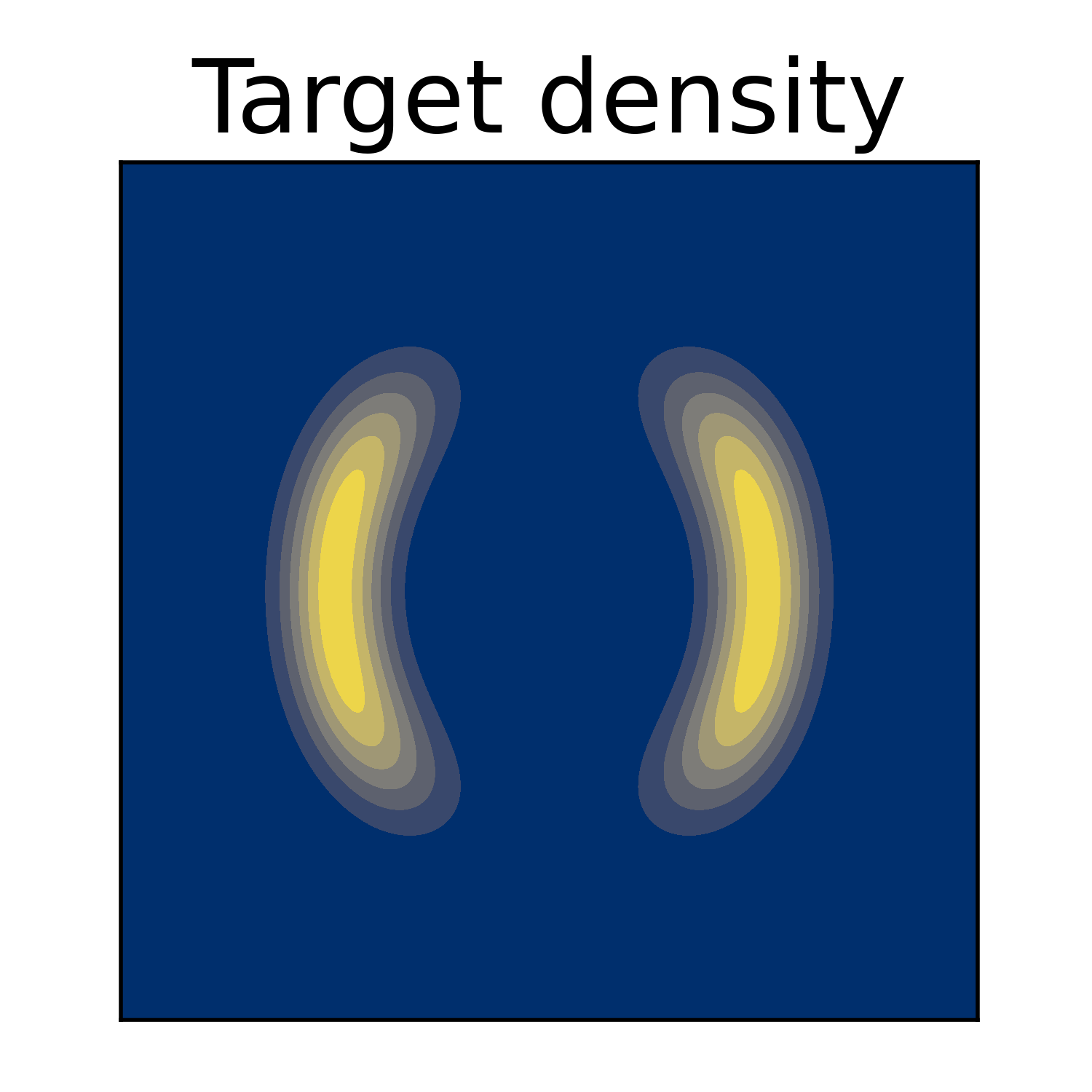

Example: Gaussian with Full Covariance

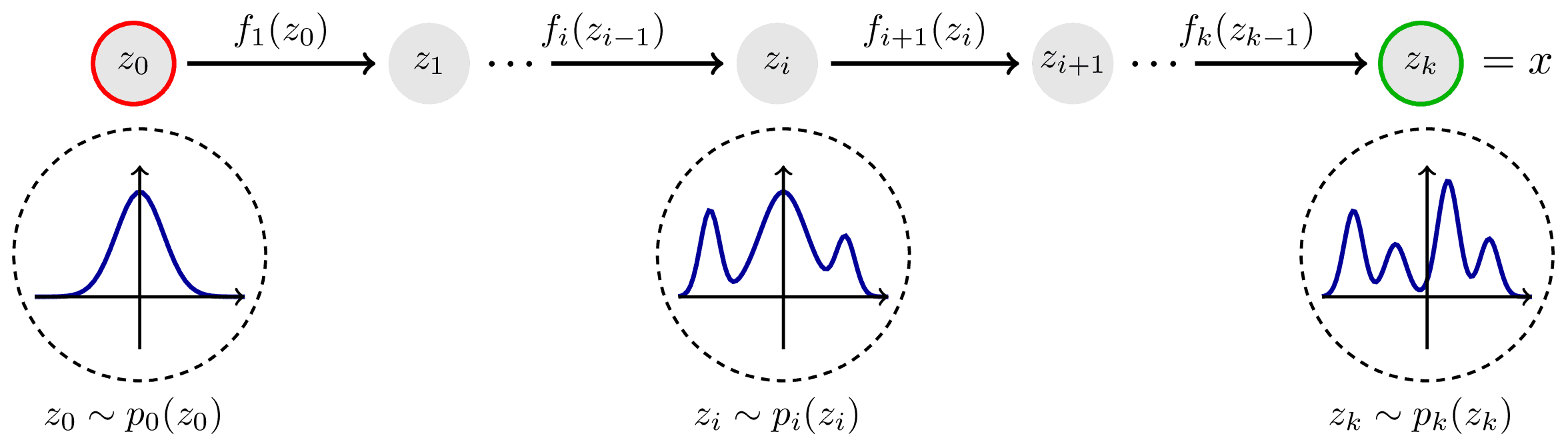

Normalizing Flows

Refresh

Given a invertible function \(f: \mathcal{X} \mapsto \mathcal{Y}\) and a simple distribution \(p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}})\), we can compute the density of \({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}\) as

\[ \begin{aligned} p({\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}) &= p({\textcolor{input}{\boldsymbol{x}}}) \left| \det \left( \frac{\partial f^{-1}}{\partial {\textcolor{output}{\boldsymbol{y}}}} \right) \right| \end{aligned} \]

We need to build \(f\):

- complex enough to approximate the true posterior

- simple enough to be able to compute the determinant of the Jacobian

Idea: Transform a simple distribution into a complex one using a sequence of invertible transformations

Normalizing Flows

Normalizing Flows: Example

Applications

Applications of Variational Inference

Variational inference is used as inference method in many models:

- Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA):

- Topic modeling

- Discovering topics in a collection of documents

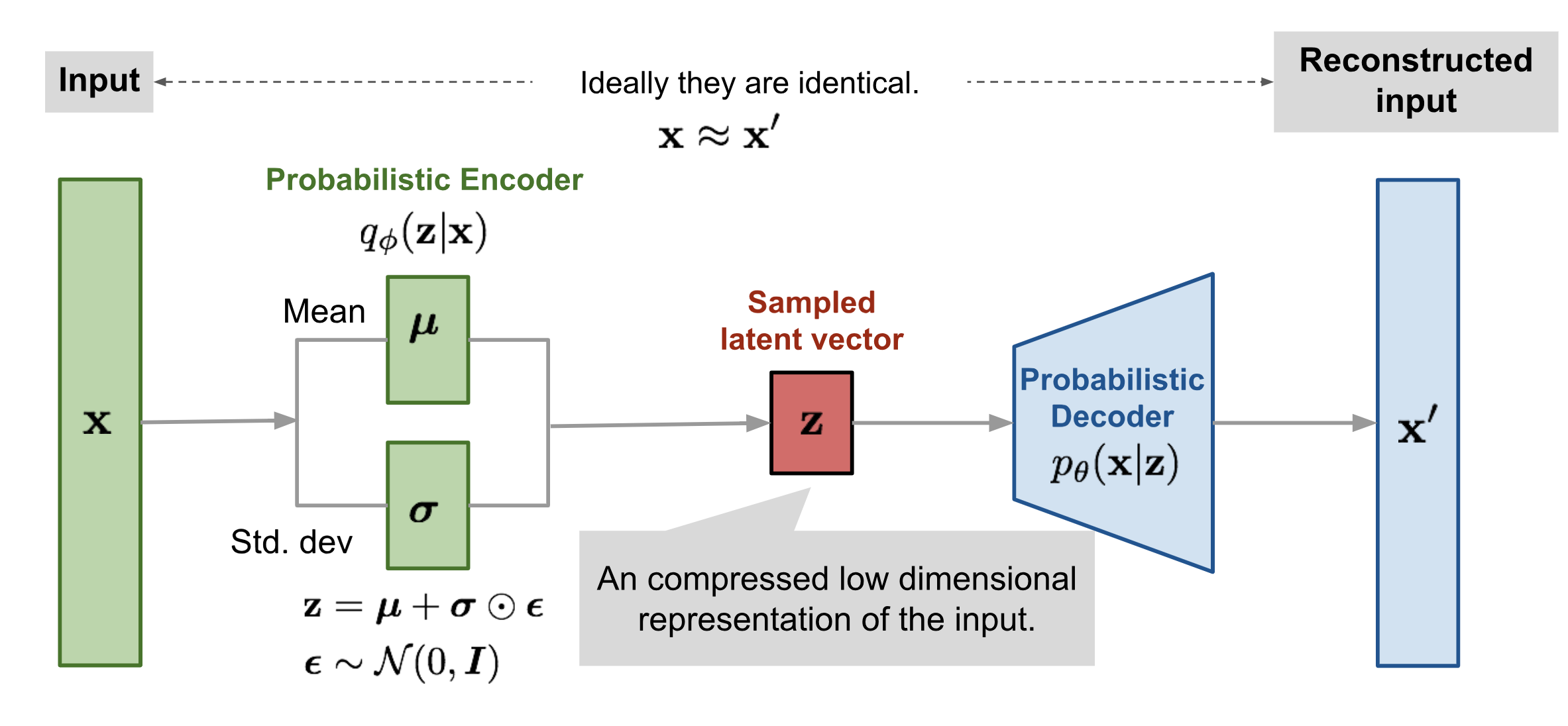

- Variational Autoencoders (VAE):

- Generative models

- Learning representations of data

Simone Rossi - Advanced Statistical Inference - EURECOM